Observable JavaScript

NotebooksThe JavaScript dialect used in Observable notebooks is almost—but not entirely—vanilla. This is intentional: by building on the native language of the web, Observable is familiar. And you can use the libraries you know and love, such as D3, Lodash, and Apache Arrow. Yet for dataflow, Observable needed to change JavaScript in a few ways.

Note

Observable JavaScript is used in notebooks only. Observable Framework uses vanilla JavaScript.

Here’s a quick overview of what’s different from vanilla.

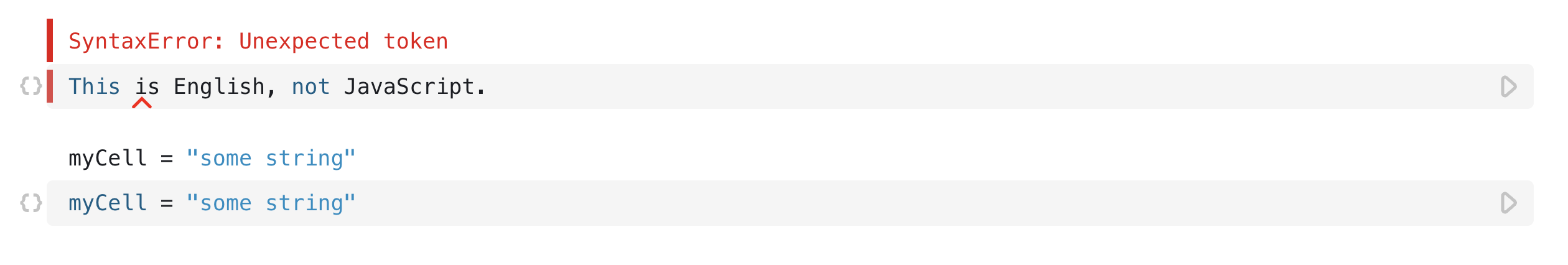

Cells are separate scripts

Each cell in a notebook is a separate script that runs independently. A syntax error in one cell won’t prevent other cells from running.

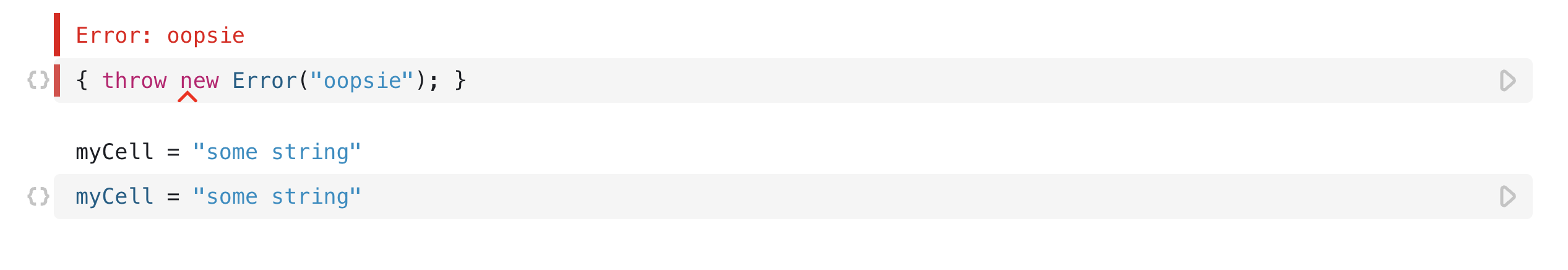

The same holds true for a runtime error:

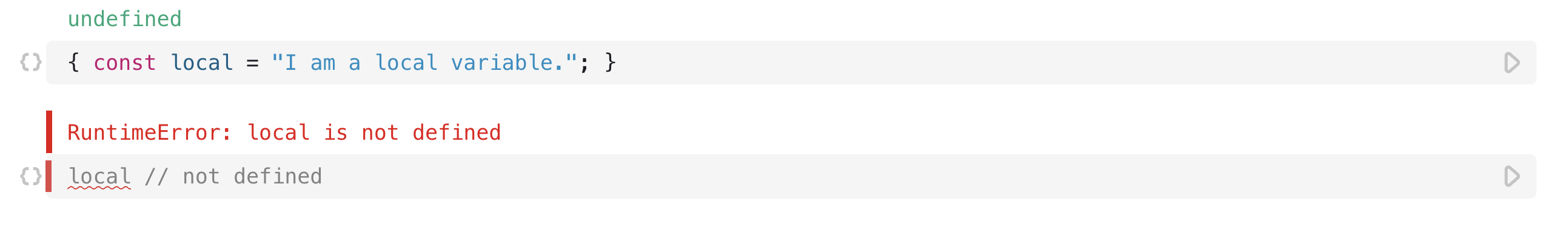

Likewise, local variables are only visible to the cell that defines them. Here in the following screenshot, you can see the constant local is defined within curly braces and is therefore local to the cell/block. Therefore, when the variable is called in the next cell, there is a runtime error:

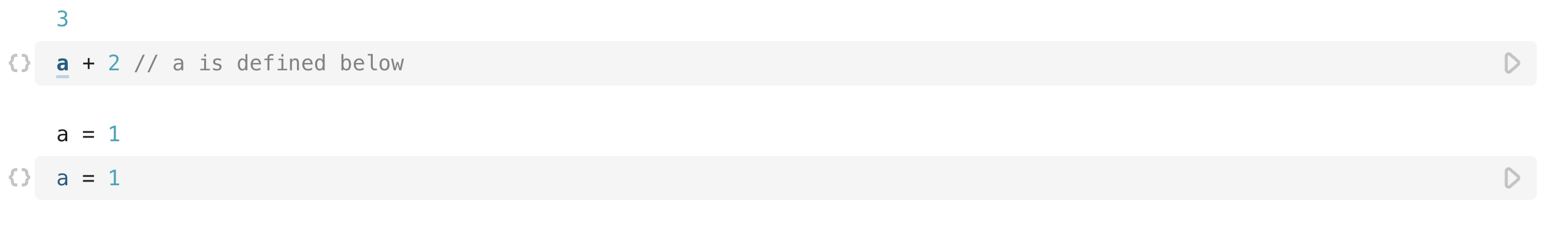

Cells run in topological order

In vanilla JavaScript, code runs from top to bottom. Not so here; Observable runs like a spreadsheet, so you can define your cells in whatever order makes sense.

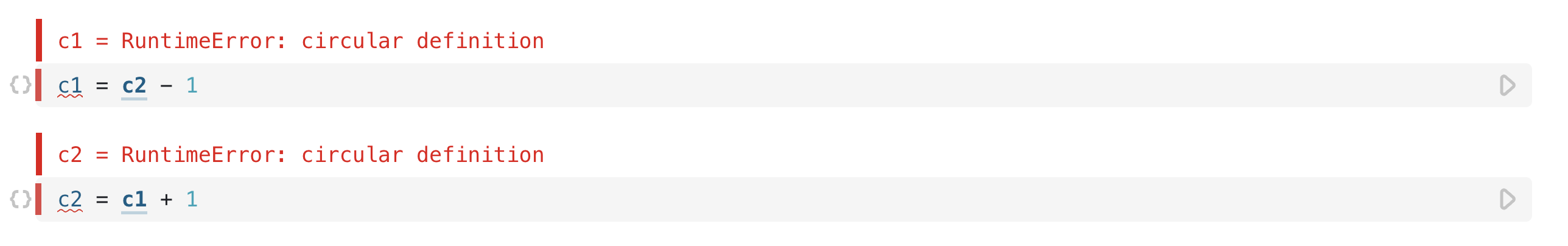

By extension, circular definitions are not allowed:

Cells re-run when any referenced cell changes

You don’t have to run cells explicitly when you edit or interact—the notebook updates automatically. Run the cell below by clicking the play button , or by focusing and hitting Shift-Enter . Only the referencing cells run, then their referencing cells, and so on—other cells are unaffected.

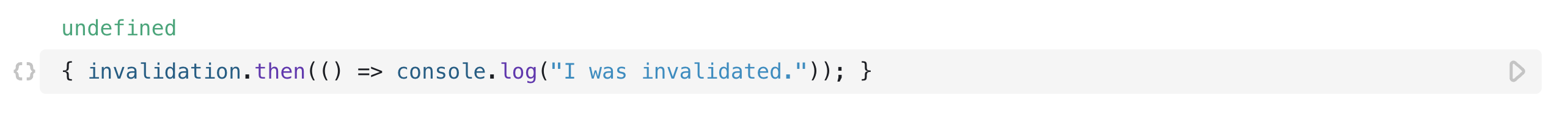

If a cell allocates resources that won’t be automatically cleaned up by the garbage collector, such as an animation loop or event listener, use the invalidation promise to dispose of these resources manually and avoid leaks.

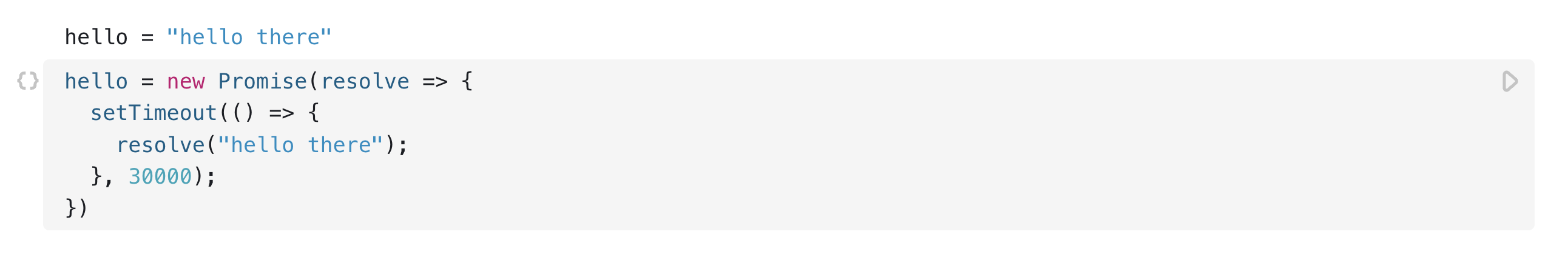

Cells implicitly await promises

You can define a cell whose value is a promise:

If you reference such a cell, you don’t need to await; the referencing cell won’t run until the value resolves.

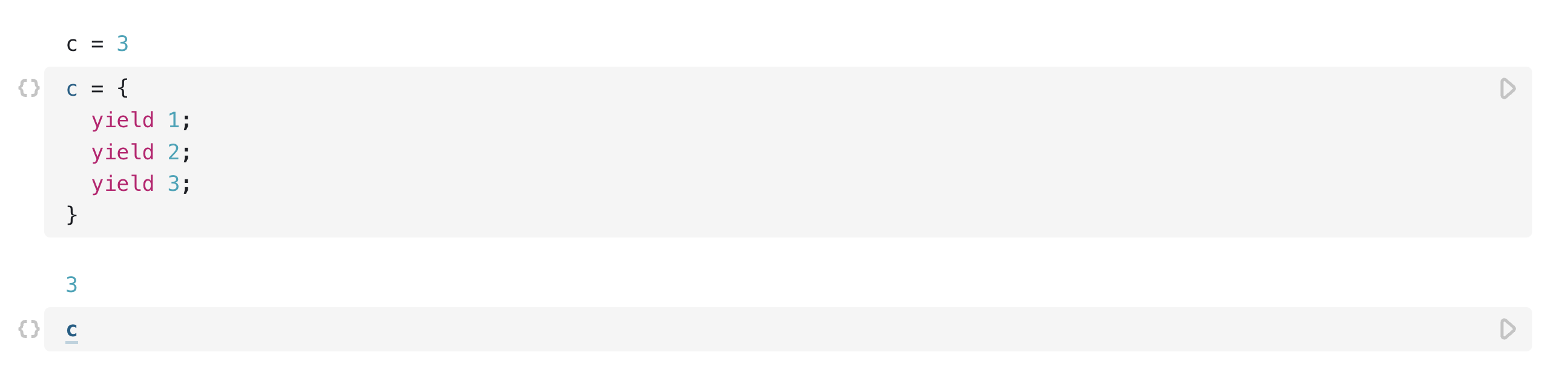

Cells implicitly iterate over generators

If a cell yields, any referencing cell will see the most recently yielded value.

Also, yields occur no more than once every animation frame: typically sixty times a second, which makes generators handy for animation. If you yield a DOM element, it will be added to the DOM before the generator resumes.

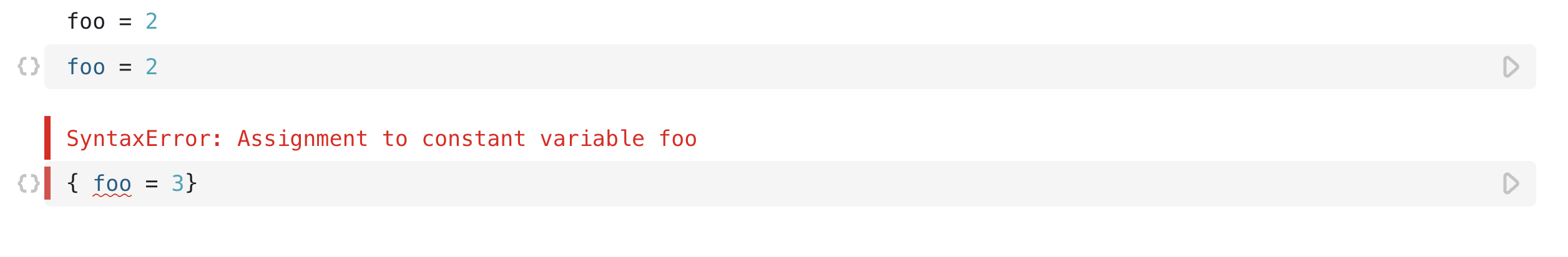

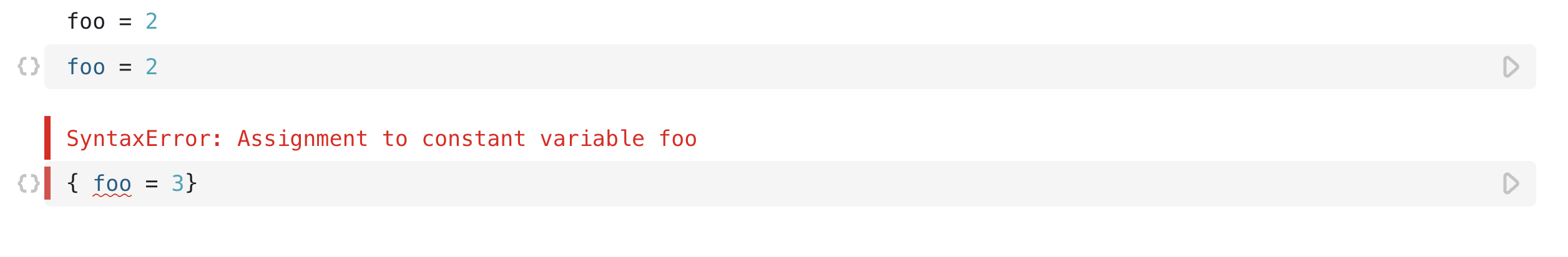

Named cells are declarations, not assignments

Named cells look like, and function almost like, assignment expressions in vanilla JavaScript. But cells can be defined in any order, so think of them as hoisted function declarations.

You can’t assign the value of another cell (though see mutables below):

Cell names must also be unique. If two or more cells share the same name, they will all error:

Note

Observable doesn’t yet support destructuring assignment to declare multiple names, but we hope to add that soon.

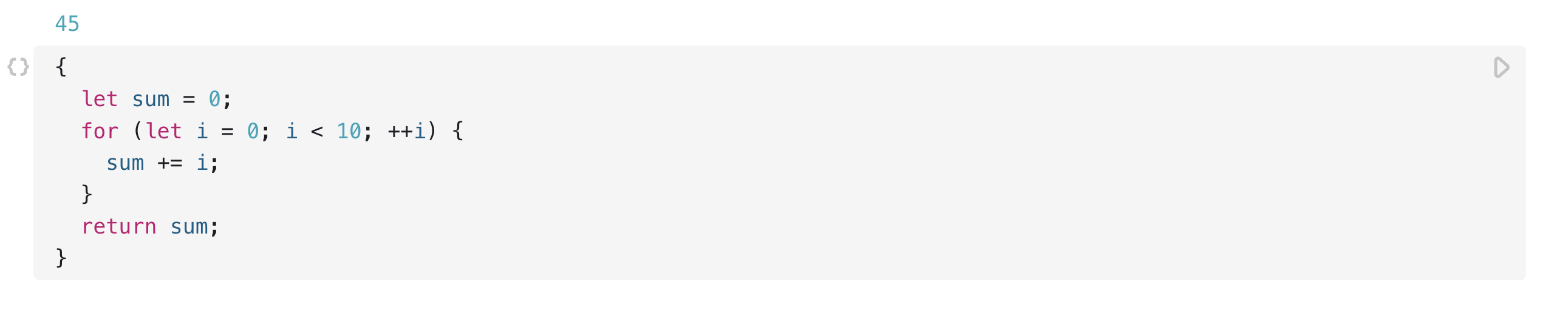

Statements need curly braces, and return or yield

A cell body can be a simple expression, such as a number or string literal, or a function call. But sometimes you want statements, such as for loops. For that you’ll need curly braces, and a return statement to give the cell a value. Think of a cell as a function, except the function has no arguments.

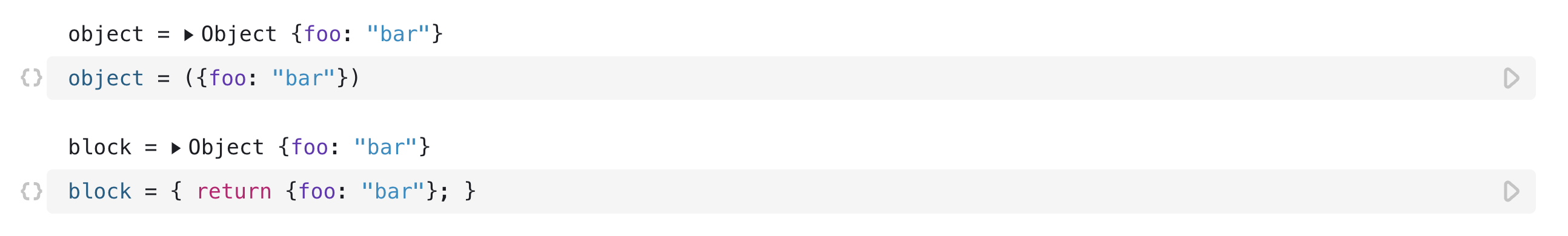

For the same reason, you’ll need to wrap object literals in parentheses, or use a block statement with a return:

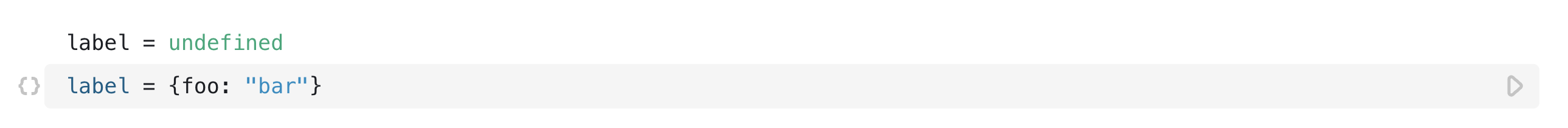

The below cell is interpreted as a block with a single labeled statement, followed by a string literal expression. The cell value is undefined because the block doesn’t return anything.

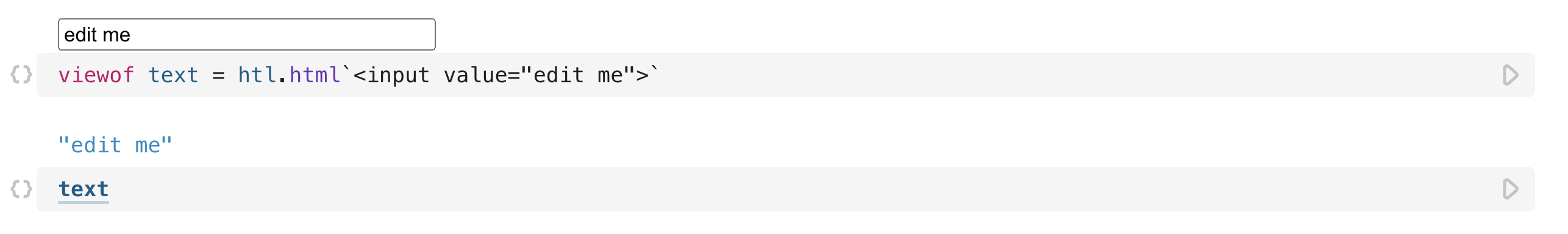

Cells can be views

Observable has a special viewof operator which lets you define interactive values. A view is a cell with two faces: its user interface, and its programmatic value.

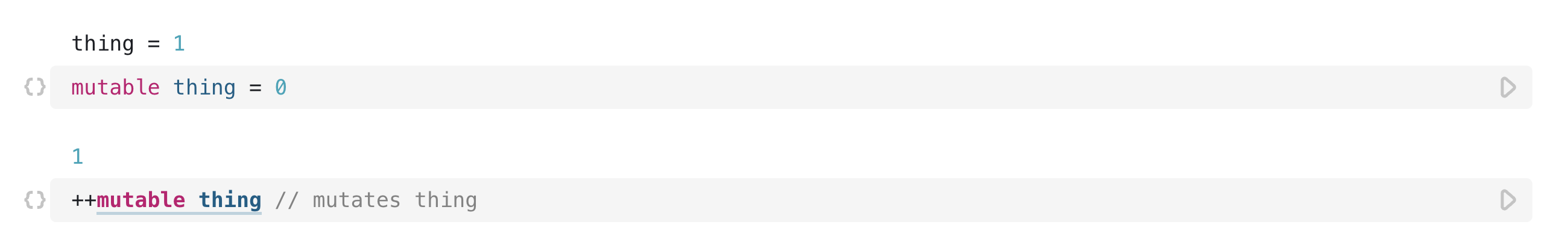

Cells can be mutables

Observable has a special mutable operator so you can opt-in to mutable state: you can set the value of a mutable from another cell:

Observable has a standard library

Observable provides a small standard library for essential features, such as a reactive width and Inputs.

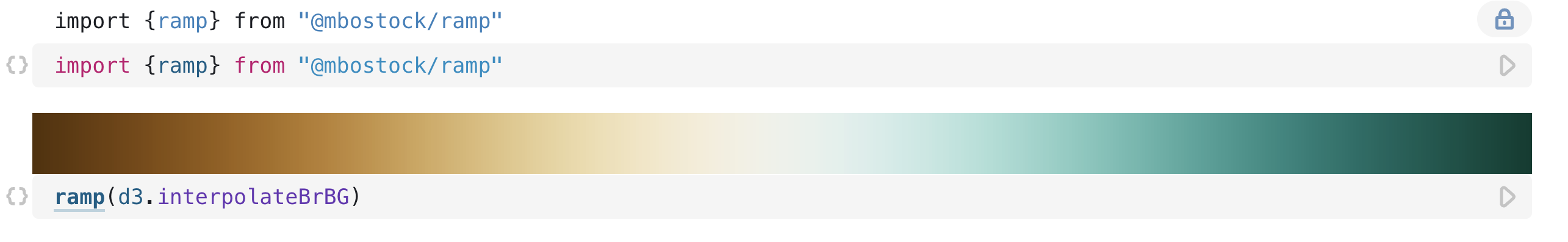

Cells can be imported from other notebooks

You can import any named cell from any notebook, with syntax similar to static ES imports. But Observable imports are lazy: if you don’t use it, it won’t run.

Also, you can import-with, which allows you to inject cells from the current notebook into the imported notebook, overriding the original definition. You can treat any notebook as an extensible template!

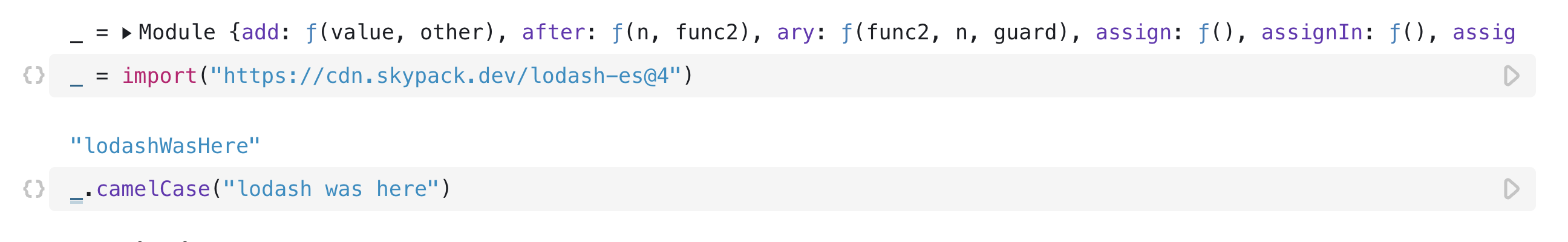

Static ES imports are not supported; use dynamic imports

Since everything in Observable is inherently dynamic, there’s not really a need for static ES imports—though, we might add support in the future. Note that only the most-recent browsers support dynamic imports, so you might consider using require for now.